Home » 2006 » Reclamation Project » About » Mary Jo Aagerstoun Essay

RECLAMATION PROJECT ESSAY

By Mary Jo Aagerstoun, Ph. D.

Xavier Cortada’s Reclamation Project (2006-present) is a long-lived community activation ecological art intervention. Together with its spinoffs, Native Flags and Flor 500, the Reclamation Project has engaged scores of Floridians, including most of the public school students in Miami-Dade County, in learning about and addressing the widespread disappearance of Florida native vegetation. The Reclamation Project continues today to carry out its original focus on the engagement of local residents in the gathering, nurture and planting of mangrove propagules, as a key ongoing element of the Patricia and Phillip Frost Miami Science Museum’s volunteer coastal restoration programming.

Origins of the Reclamation Project

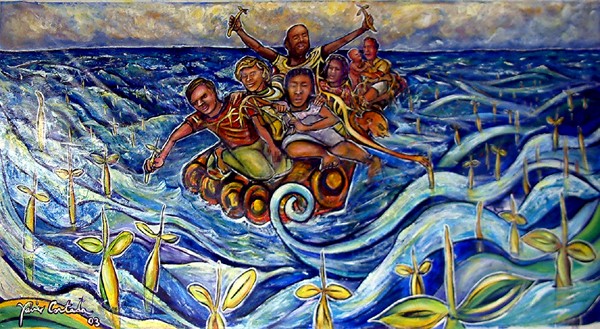

Xavier Cortada has been fascinated since childhood with mangroves, especially with the propagules’ strange shape and self-planting habit. He came to think of the seeds as a metaphor for the immigrant: floating to a new shore, putting down roots and contributing to a fertile new home community. Mangroves began to appear as a central theme in his works in 2003 with a series of commissioned mural-sized paintings, several of which are permanently installed in government buildings in Tallahassee and Miami. Mangroves dominated Cortada’s work for the next decade: in commissioned works for gallery installation, as public art, and culminating in his multifaceted ecological art intervention, the Reclamation Project.

Figure 1: Xavier Cortada, “The Journey,” 55″ x 116″, Acrylic on Canvas, 2003.

In 2006, Cortada witnessed the violent uprooting of mangrove forests near his Florida Keys retreat. This singular event propelled the artist to create The Reclamation Project. Motivated to take action, Cortada initially wanted to focus on replanting the area in the Keys where he had witnessed the mangrove forest destruction.

Since he had little information on how to plant mangrove propagules successfully, Cortada solicited assistance from marine biologist Gary Milano, the Habitat Restoration Program Director for the Miami-Dade County Department of Environmental Resources Management whose responsibility it was to plant mangroves in areas designated as “mitigation” sites. A “mitigation” site is public land where mangroves may be planted in the numbers taken down under a permit provided by the State for reasons acceptable to the State. Mangroves are highly regulated because of their importance in riparian ecologies, including as nurseries for sea life, as well as their role in protecting land from erosion.

Cortada credits University of Miami classmate Marsha Colbert, Director of the Florida State Department of Environmental Resources, Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve, for introductions to Gary Milano, the DERM scientist who became his primary science collaborator; and to art historian and founder of EcoArt South Florida, Mary Jo Aagerstoun in 2007, a watershed Cortada points to as the origin of his understanding that what he was doing intuitively, was a particular art form called “ecological art.”

Cortada learned from Milano that his initial idea to plant full-grown mangroves at the site where he had witnessed the trees’ removal would not work because the fragile trees could not withstand the strong wave action at that location. The collaboration with Milano, and access to his expertise on mangrove husbandry, became central to the project’s success. Milano continued as primary science advisor to the project until his retirement in 2013.

Later in 2006, The Bass Museum hosted the first museum-based installation of living mangrove propagules, together with two videos documenting the mangrove forest destruction Cortada had witnessed. At the same time, in fall 2006, the first full blown Reclamation Project began as an installation in shop and restaurant windows along the pedestrian area on Lincoln Road in Miami Beach, just in time for Miami Beach’s Art Basel 2006 in early December.

In fall 2006, volunteers first collected propagules, installing them in grids of water-filled plastic cups on the insides of storefront windows along Lincoln Road, Alton Drive and Ocean Drive in Miami Beach, as well as in a condominium lobby used for the Scope Art Fair during Art Basel, 2006. Later, when the propagules matured, volunteers returned them to a Milano-selected water’s edge site, planting them ritually, by repeating the phrase: “I hereby reclaim this place for Nature.”

This basic process of volunteer involvement in gathering mangrove propagules, displaying them in grid formations on the windows of shops and restaurants along Lincoln Road, and planting them weeks later, under Milano’s professional supervision in public land “mitigation” areas, continued for consecutive years. The entire project ultimately moved to the Miami Science Museum and became the basis for MUVE (Museum Volunteers in Education), the Science Museum’s citizen volunteer coastal restoration program.

In addition to Cortada as the project’s overall director, and Milano as the supervisor of propagule gathering and planting, Jackie Kellogg recruited volunteers and selected and trained team leaders on the project’s science, structure and process, as well as on volunteer supervision. The team leaders also received extensive instruction on logistics, documentation, and how to train volunteers in approaching and explaining the project to prospective hosts in shops and restaurants along Lincoln Road. The volunteers were also trained on how to install the propagules in their containers in the storefront windows.

Cortada stresses that:

Each aspect was assigned to the person best prepared, and most experienced. All participants were educated to become “eco emissaries”— the volunteers, the propagules’ hosts, and, most importantly, the public encountering the propagules themselves. And the grand finale was a ritual where volunteers planted while repeating the phrase: “I hereby reclaim this land for nature.”

Every year, from 2006-2012, the original Reclamation Project model was repeated along Lincoln Road in Miami Beach. Since December 2007, when the Miami Science Museum (MSM), now the Patricia and Phillip Frost Museum of Science, hosted the first installation of 1,111 propagules, the project has continued to be implemented, exactly as originally designed, as a special program of MSM’s Museum Volunteers in Education (MUVE). MUVE now operates a county wide in-school program, featuring the grid installation design, and the volunteer propagule gathering and planting model, developed for the first appearance of the Reclamation Project on Miami Beach in 2006. The project has also been hosted in many other locations across the State and beyond, always following the original model.

Figure 2: mangrove propagules in store front window. Lincoln Road, Miami Beach, FL, 2007. Photo; Xavier Cortada

Figure 3: Planting propagules at Bear Cut, Key Biscayne. Miami. 2007. Photo: Xavier Cortada

The Reclamation Project’s aesthetics: art, activism or both?

Cortada sees the Reclamation Project as both art and activism. He believes art was the best way at the time to bring the destruction of mangrove forests to high-profile attention, and describes moving intuitively toward a fusion of performance, multi-media installation and social engagement art as the central aesthetic methods.

In retrospect, I can see that I was creating a model that expressed that we don’t have to know everything to make change. I did not have a wide and deep knowledge of the art history of contemporary aesthetic approaches as a tool box. I knew the mural approach I had used for a long time in other social engagement situations would not work in this context. I just followed my passion and sense of urgency to help as many people as possible to learn as much about the importance of mangrove forests as I was in the process of doing, and thus to inspire them to care and act as they learned.

Cortada’s “performative” approaches echo methods of the “happenings” of the 1950s and ‘60s “art into life” movement, the 1990s community-centered “social turn” to art.

Performance. The Reclamation Project is most similar to the “happenings” of the 1950s and 1960s artist and writer Allan Kaprow named in his classic book Assemblage, Environments and Happenings: a collage form of performance, and radical prototype of what later became full-blown performance art, in which the audience is a participating component, and which is often performed in “nontraditional” (e.g., outside art gallery or museum) settings.

Many audience types were drawn into, or engaged with the Reclamation Project in various ways, much as audiences for the 1960s “happenings” were drawn in. There were the original volunteers that annually brought propagules to Lincoln Road, and later planted them in permitted mitigation locations; the Lincoln Road shopkeepers and restaurateurs who hosted the project; the general public who encountered the oddly shaped plants in shop windows, and stopped long enough to read about them, or entered a store to ask; the museum visitors at the Bass Museum in 2006 who saw both the grid of propagules and the video showing the mangrove forest destruction in the Keys that had inspired the project to begin with; and the hundreds more students of all ages, families and others who became active volunteers in caring for the propagules and planting them, continuing to do so through museum and public school programs up to the present, with no end in sight.

Time-based Art. For the Reclamation Project, a broad definition of this practice is apt: “us(ing) the passage of and the manipulation of time as [an] essential element.”10 The movement and manipulation of the Reclamation Project’s living media (propagules), the project’s organization, reception and continuation over time, the multiplicity of sites, and what happened at each (collection of propagules, finding and preparing display locations, and, finally, their ritual planting), all combine to resemble many types of time-based performance art–from the “Happenings” of the late 1950s down to today’s performative “social practice” projects.

The process was also described as “choreography,” a time-based art, in a (2007) essay, in which:

The artist acts as choreographer of collaborative action as well as premier danseur. The resulting “dance” is enacted by a corps de ballet including …citizens …scientists … public officials; and whole institutions from … museums to local schools and organizations, where the public learns how to carry the dance forward. The public becomes both dancer and audience.

Social Sculpture. The Reclamation Project refers to the social sculpture genre in its combination of performance with two other characteristics of the traditional sculpture genre–the “additive” (pastiche or assemblage), and the “kinetic”—deployed together to engage social and institutional processes and individuals, as sculptural media. The term “social sculpture” was first used by German artist Joseph Beuys in the 1960s. This art practice is the basis for much of what is known today as “social practice” art.

The artist points out that:

The project was a kind of pastiche or weaving of social and material/natural processes. We had to listen to each other, to the voices of the experts, the volunteers, and be quickly responsive. We had to understand what tools we needed at various points. We needed to quickly understand barriers to moving forward, and be nimble in avoiding them, whether they were bureaucratic/organizational processes or natural processes. And we had to accept when it was time to let go and let Nature move the natural materials of the sculpture forward in their natural settings, and even to let go of the project entirely as my artist’s creation.

Installation Art. An authoritative definition from London’s Tate Gallery characterizes installation art as: “…mixed-media constructions…designed for a specific place or for a temporary period of time…a complete unified experience, rather than a display of separate, individual artworks.” The Reclamation Project’s use of the “installation art” approach was evident at two points: first, in the grid of propagules arranged in water-filled plastic containers attached to glass windows or walls. The second “installation” was the planting of propagules where they would thrive, their roots protecting land and providing refuge and food for native marine creatures.

The Grid. Art theorists and critics see the grid as announcing the presence of art, specifically, modernist art. In 1979, influential Columbia University art historian and critic, Rosalind Krauss, pronounced that: “The grid functions to declare the modernity of modern art…flattened, geometricized, ordered, it is anti-natural, unreal. It is what art looks like when it turns its back on nature.”

Cortada notes that the use of a grid installation format intentionally juxtaposed the living propagules with the geometrics of the urban site where forests of mangroves once had stood:

The cups were intentionally placed in a grid format to juxtapose the organic, living material with the city block grid pattern. Placing them in storefront windows–hard edged rectangles, themselves–was immediately seized upon as not only geometrically appropriate, but also a great location, because the grids could be seen from both the street and the store interior, so it was likely that thousands of people would see them. The grid shape differentiated it enough so it could be seen as–and called—“art.”

Juxtaposing the living propagules with flat geometry not only announced the project as art, it also underscored the project’s message that living nature was not welcome in human beings’ “anti-natural” urban habitat; and could only survive there with constant human attention.

The Surprise Factor

The effect of surprise in causing audiences to stop and think, is similar to the theoretical construct also known as V-effekt, alienation effect, or “distantiation” effect developed by dissident playwright Bertolt Brecht to inspire resistance to the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany in the 1920s and ‘30s by helping theater audiences identify theatrical “tricks of the trade” used by Nazi spectacle producers to emotionally manipulate people into supporting the Reich. Activist artists have since widely adopted this distantiation/surprise effect to call attention to political manipulation, both in and out of the formal theater context. The intent still is to provoke a social-critical response by “mak(ing) the familiar strange.” Cortada credits art historian Mary Jo Aagerstoun, for helping him see that his intuitive use of the grid installation form in non-art settings echoed an aesthetic tactic of “making strange” developed by Bertolt Brecht nearly 100 years ago.

Hanging the propagules in commercial locations in geometrically arranged, transparent, water-filled plastic containers indeed succeeded in drawing curious attention from passers-by, which was intentional on the artist’s part. Cortada notes:

Figure 4: The grid installation format. Tampa Preparatory School, Tampa, FL. 2009. Photo: Xavier Cortada

It did surprise! People go to the museum or gallery expecting to find objects that are intriguing or different, but not in a shoe or book store. It has nothing obvious to do with the purpose of the business, so why is it there? It surprises them, grabs their attention long enough to prompt further inquiry, and, we hope, some change of perspective, as the observer becomes aware by reading the palm card hanging with the plants that these little mangrove shoots can only survive in an urban setting if human beings care for them.

Whether any long-term positive effects on viewers ensued from these surprise encounters is unknown. Financial and other limitations did not allow for evaluation. Cortada noted:

No, we can’t prove that seeing the propagules in unlikely places had the effect we wanted. [But] if you consider how many people visited Lincoln Road over the six years we did the project there, we could estimate that about 200,000 people were exposed to the project. I am satisfied with that.

Figure 5: Passersby are intrigued by mangrove propagule installation. 2007. Photo: Xavier Cortada

The Reclamation Project’s science

A crucial aspect of effective ecological art is its firm basis in science. An ecological art work must integrate scientific analyses of environmental degradation in order to be either neutral or ameliorative in its effect on the natural environment in which it is sited. Ecological art includes a wide range of practices, which all seek to make “visible” the “invisible” processes and causes of degradation. The Reclamation Project incorporates important aspects of the best science about restoration of mangrove stands, has ameliorative effects, and educates diverse and numerous audiences. Nevertheless, the artist points out:

The Reclamation Project was always pro-science. But I never conceived of it as a science project. It was always art in the service of science. My intention was always to help people vote the way scientists think. My sense was they had to be immersed in something so ubiquitous that it had become a backdrop, something familiar, but not understood.

The “something so ubiquitous” was the mangrove: familiar to the point of invisibility, and yet critical to the protection of Florida land. In 2006, the same year the Reclamation Project began, Al Gore released his documentary Inconvenient Truth across the country. Cortada’s approach differed from Gore’s in Inconvenient Truth. The Reclamation Project was not a response to climate disruption scientific discourse, but, rather, to species loss. Cortada explains:

The Reclamation Project took form at a time when skyscrapers were popping up everywhere along Miami shorelines. My direct witness of the environmental destruction being done to make this growth happen moved me to action. There is no doubt that [Al Gore’s film] was part of the background as the project formed in my mind. As were the many conversations with scientists on the warming effects they were seeing during my NSF artist residency in Antarctica. As the project matured, we got more deeply into mangroves’ climate-related importance, such as carbon sequestration and storm surge protection.

Cortada frankly states that, though he has studied and taught biology, he does not consider himself to be a biologist. He sees the Reclamation Project as an art-based mobilization and engagement effort, not a “science project:”

I had been a full time artist for ten years when The Reclamation Project was launched. If my role in the project was anything other than as an artist, it was more as a social scientist, than as a biologist, although I am very comfortable with science and in science milieus. I was more a mobilizer, an engager, an awareness builder, which is totally based in the two decades I spent working with participatory “message” mural projects aiming at community engagement. And, the fact that the Project now resides at the Miami Science Museum, and has required no “science tweaking” at all, speaks, I believe, to how adequate and well integrated the science basis was.

The Reclamation Project’s community engagement

Cortada used a “learn together” approach to community engagement, rather than a more traditional “charrette” process. Cortada explains:

It was more like how an art studio functions: the artist provides design and methods, and studio assistants carry out the project. Studio assistants often come up with innovative ways to carry out a design. We learn together. I chose this approach not because I didn’t consider, or don’t value the charrette and other approaches to community involvement that elicit community desires as the basis for action–I have done this often throughout my career—but, in The Reclamation Project there was a sense of urgency. People needed to experience firsthand because there really wasn’t experience there to draw on. I didn’t want The Reclamation Project to be only an awareness exercise. I wanted to help advance a culture of caring.

Cortada felt the art studio organization approach was the best way to “help people act” and “advance a culture of caring.” Cortada‘s intuition was that “everyday people” can most quickly arrive at a place of action through direct witness, by “getting their fingernails dirty” and learning together.

Figure 6: Planting mature propagules. Bear Cut, Key Biscayne, Miami. 2007. Photo: Xavier Cortada

Did it work?

The evidence that the Reclamation Project has started an ongoing “learning together” conversation, where the engaged community and the “teacher” exchange insights and practical ideas, is apparent in its continuing vibrant existence across many community platforms. The project illustrates Wallace Heim’s concept of “slow activism,” where a successful “slow activist” exchange “…works not only in the immediacy of the [first] event,” but in an ongoing way, in “unforeseen” future circumstances.

Xavier Cortada believes the 2006 Reclamation Project model, has become an ongoing “slow activist” exchange that is realizing the process he wanted to see at the beginning:

I have loved learning about the concept of social sculpture and slow activism. I see The Reclamation Project as a great combination of both of these, even if I created the project without knowing these art genres even existed! The project is still very much alive! The conversation continues, right now! In and out of institutions. Between individuals, between students and teachers, between artists and other art folk. It is Slow Activism!

One can point to the instantly recognizable characteristics of succeeding generations of the Reclamation Project as evidence that the project is “working.” Each new appearance melds established scientific methods, teacher-learning-from-pupil-learning-from teacher pedagogy, and seemingly diametrically opposed aesthetic approaches: the choreographed movement of people and living plants, to Nature’s cadence; the grid installation form; the “slow activism” weaving together unlikely partnerships and social processes; and the mobilization of surprise as an audience engagement tactic.

Cortada feels the project has not suffered from lack of a formal evaluation, and that the Reclamation Project did successfully integrate aesthetics, science and community engagement:

Whether this project has “worked” is a hope of mine, and can’t necessarily be proven. There are much more efficient ways to accomplish reforestation than what The Reclamation Project did. Using seedlings purchased from commercial nurseries, Gary Milano carried out his job to plant mangroves with prison labor. That is both efficient and inexpensive, though, of course, this use of prison labor can be questioned. Nonetheless, the Reclamation Project cannot be said to have been created as an experiment that showed the way to restore mangrove forests either more scientifically or more efficiently. It was created to engage community.

Figure 7: The grid of propagules at the Miami Science Museum. Miami. 2007. Photo: Xavier Cortada

Cortada reported that there were a few small surveys here and there, especially if a grant was involved. But no overall evaluation was ever done on how the project worked, though, as in most of his work, a voluminous archive documenting the process of creation in most of the sites exists on various web-based platforms. Cortada believes the continuing life of the project is proof of its success:

The best outcome, for me, is that the project now happens without me. It is being done on an ongoing basis as a central project of the education program and volunteer involvement at the Science Museum. I think it is also significant that its curriculum is in every public school in the county! In most cases now, the project does not have a high profile as art. It exists primarily as a science education initiative. Nevertheless, I continue to see it as both art and activism, in the service of science and the environment.

Mary Jo Aagerstoun, Ph. D. is an art historian who studies contemporary art that engages important public issues. She lives in West Palm Beach, FL and wrote “Xavier Cortada’s Reclamation Project” as one of the chapters of her upcoming book on eco-art.

Footnotes:

1 Xavier Cortada, “Florida Native Plant Society presentation: Native Flags,“ accessed July 26, 2016, httpwww.xaviercortada. com/events/EventDetails.aspx?id=289283 and Xavier Cortada, “FLOR 500 About the Project,” accessed July 26, 2016, http://cortada.com/archives/xaviercortada/index.html%3Fpage=FLOR500_about

2 https://www.frostscience.org/museum-volunteers-for-the-environment/ Downloaded 8-13-2018

3 See State regulations on removal of mangroves, and mitigation at: http://www.flwaterfront.com/information/mangrove-regulations/

4 EcoArt South Florida was a non-profit 501 c 3 organization (2007-2015) founded by Dr. Mary Jo Aagerstoun. The organization’s purpose was to advocate for bringing more south Florida artists into ecological art practice.

5 Xavier Cortada. Interview by Mary Jo Aagerstoun. July 18, 2016.

6 Xavier Cortada, “The Reclamation Project,” accessed July 26, 2017, http://www.cortada.me/2006/reclamation/bass-index.html and “Miami Beach Reclamation,” accessed July 26, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nH54uYF9ZfI and Xavier Cortada, “18-mile stretch,” accessed July 26,2016, http://cortada.com/videos/2006/18-mile-stretch.

7 Xavier Cortada. Interview by Mary Jo Aagerstoun. July 18, 2016.

8 Xavier Cortada. Interview by Mary Jo Aagerstoun. July 18, 2016.

9 See: Allan Kaprow, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Gutai Bijutsu Kyōkai. Assemblage, Environments and Happenings. New York: H. N. Abrams, 1966.

10 Source: https://www.guggenheim.org/conservation/time-based-media. Experimental film, video art and installation, sound, performance and multimedia computing are more frequently today considered “time-based” arts. The Reclamation Project exists as photo and video documentation, often used in installations, but it is really “time based” primarily in what the Guggenheim describes as having “duration as a dimension and unfold[ing] …over time.”

11 Mary Jo Aagerstoun, Ph.D. “Cortada’s EcoArt.” Online at http://cortada.com/archives/reclamationproject/?page=Artist_essay

12 For more on the origins and a currently operating social sculpture masters and PhD program in the UK see: http://www. social-sculpture.org/

13 Tate, “Art Terms,” accessed October 10, 2017, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/i/installation-art

14 Rosalind Krauss, “The Grid,” October, no. 9, 1979, 51-52.

15 Xavier Cortada. Interview by Mary Jo Aagerstoun. Online. July 18, 2016: For examples of contemporary uses of Brecht’s approach, see: Beautiful Trouble, the self-described “crash course in carnivalesque realpolitik,” which cites Brecht’s “distantiation” as central to a contemporary art-activist practice. See Andrew Boyd, ed. Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution. New York and London, 2012, 210. Online: Beautful Trouble, “Theory: Alienation Effect,” accessed November 19, 2017, http://beautifultrouble.org/theory/alienation-effect/. See also L. M. Bogad, Tactical Performance: The Theory and Practice of Serious Play. London: Routledge, 2016, 10.

16 Thomas Summer, “Changing Climate: 10 years after an Inconvenient Truth.” Science News. April 8, 2016. https://www. sciencenews.org/article/changing-climate-10-years-after-inconvenient-truth

17 Xavier Cortada, “About,” accessed November 19, 2017, http://cortada.com/archives/xaviercortada/index.html%3FAnt_about Cortada was “a recipient of the 2006-2007 National Science Foundation’s Artist Residency, when he traveled to Antarctica December 28, 2006 – January 12, 2007 to implement various art projects.” 18 A charrette is a creative process akin to brainstorming that is used to develop solutions to a problem within a limited timeframe. Charrette has become central to many community-engaging processes and practices beyond its origin in architecture and design. 19 Heim, Ibid. 187-188 20 Xavier Cortada. Interview by Mary Jo Aagerstoun. July 18, 2016